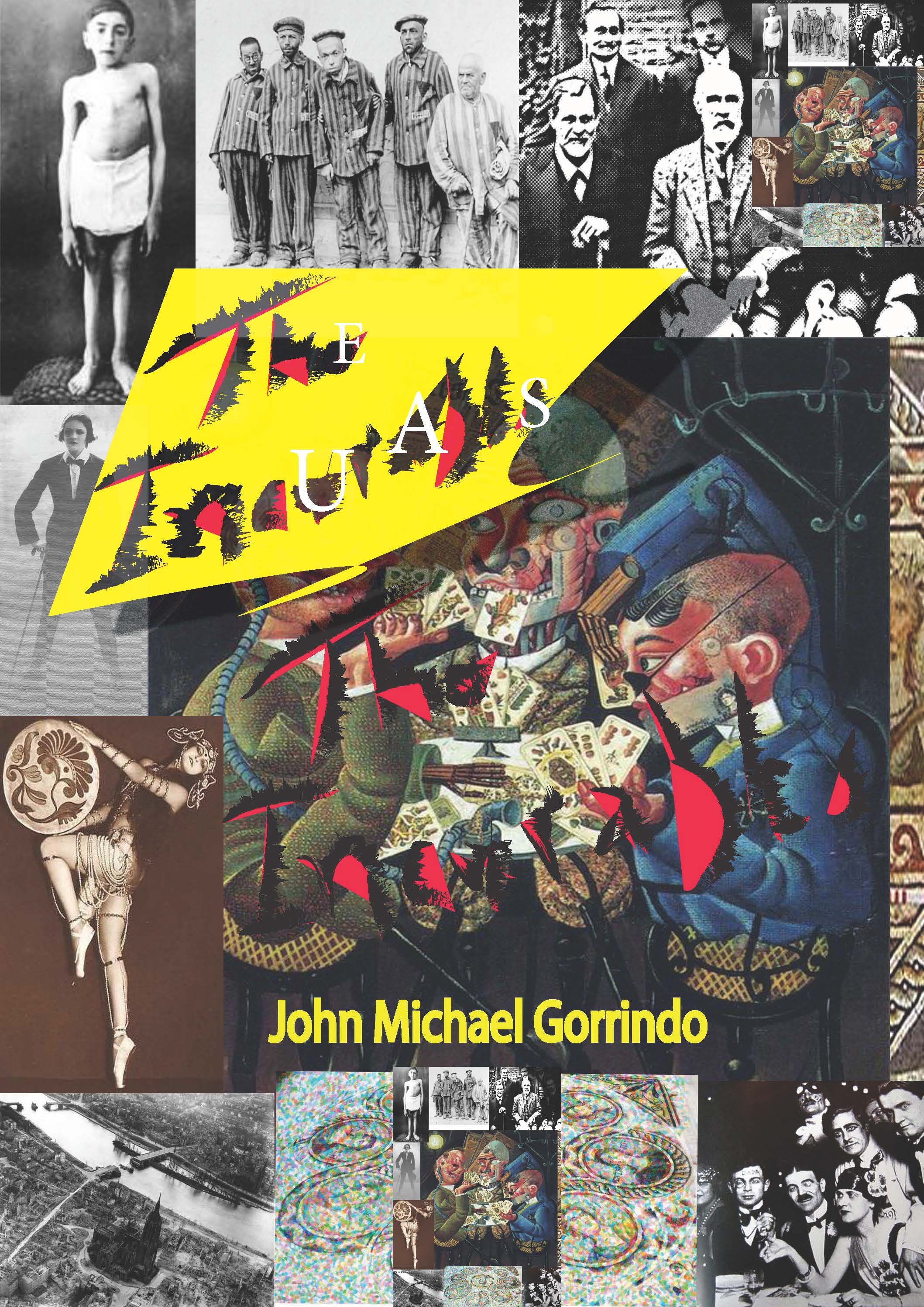

Front Cover

Back Cover

The Incurables

By John M. Gorrindo

Twenty-Four Chapters

Chapter I

“We have been silent witnesses of evil deeds: we have been drenched by many storms; we have learnt the art of equivocation and pretense; experience has made us suspicious of others and kept us from being truthful and open; intolerable conflicts have worn us down and even made us cynical. Are we still of any use? What we shall need is not geniuses, or cynics, or misanthropes, or clever tacticians, but plain, honest, straightforward men. Will our inward power of resistance be strong enough, and our honesty with ourselves remorseless enough, for us to find our way back to simplicity and straightforwardness?” Dietrich Bonhoeffer

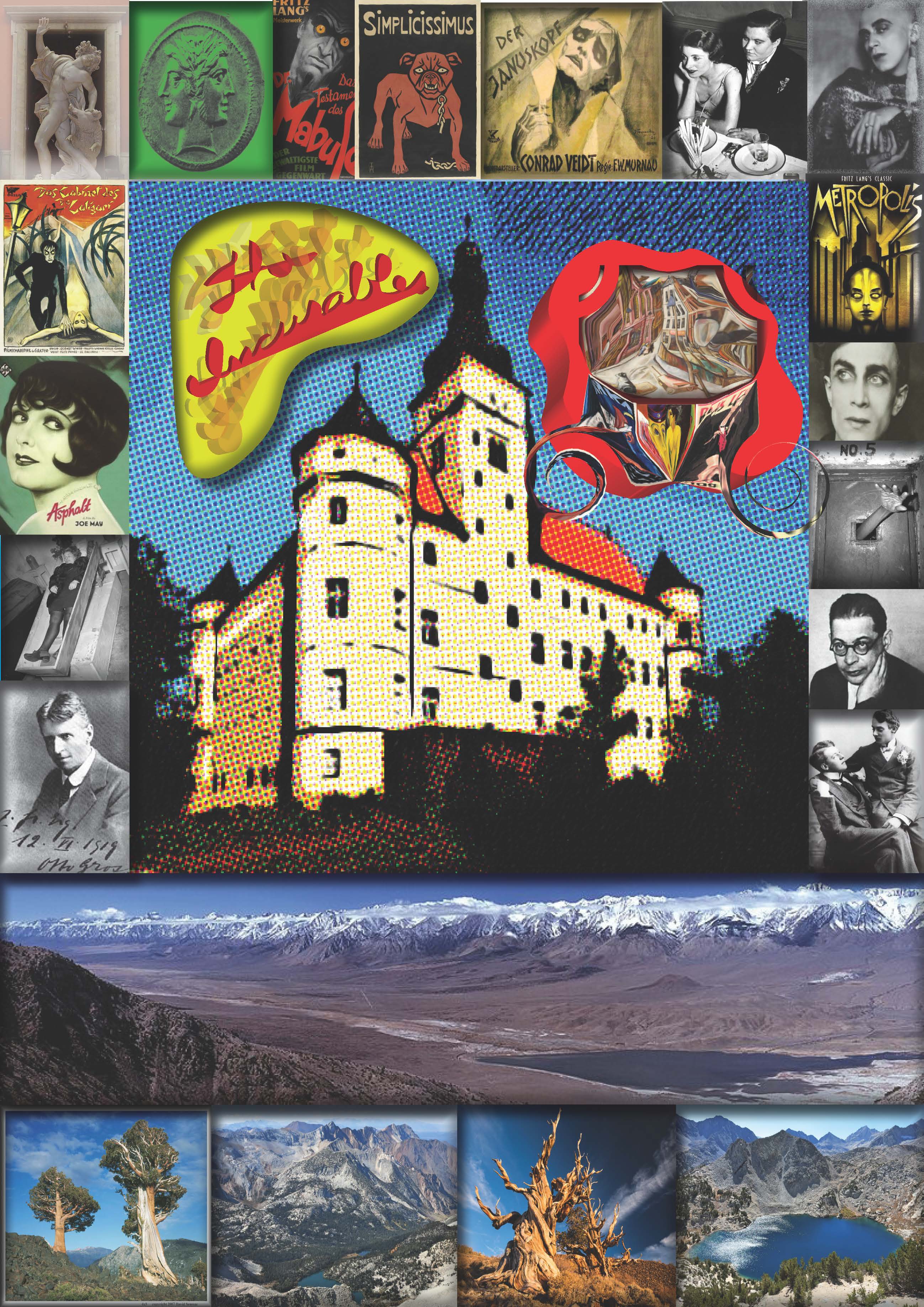

By all conventional habit of the young dismissing the old, Ulrich Hoffstetler hadn’t much left at age ninety. Almost everyone he had ever known of any personal importance was dead, including his only wife and two children. He was confined to a wheelchair due to poor circulation in his extremities, but he continued to smoke, nonetheless. A keen mind buoyed him, though, and he exercised his unabated interest in many intellectual subjects by a rigorous embrace of the internet’s encyclopedic realm. Since their inception, personal computers had always fascinated him, and he knew that without their constant provisions his mind would wither and his fragile life would simply end. He guarded his computer and its peripherals with a constant wariness, equally fearing theft as well as attack by virus. Hoffstetler did have money. His wealth was by no means ostentatious. Its origin was as purloined cash he carried out of Germany after the war in 1946, providing the seed for the small business he created that would see him through exile in America for the next fifty years. Looking ahead was always Ulrich’s salvation. Dotage comes around in finality, and he had always prepared for it. But he hadn’t quite figured on being physically incapable before a steep mental decline. So it was that father time cut out the legs from underneath him before turning him into a senile fool. Still, Hoffstetler could both afford to maintain a private residence and hire both a live-in nurse and housekeeper to help him survive independently longer than most. Mortality and Death as a rule rode in tandem upon his slumping shoulders and whispered endlessly into his ear. Such murmurings were neither directives, paranoid chatter, nor dark forebodings. They were more clarifications of what lie on the road directly ahead. Death had never been a stranger to Ulrich and had always informed his next move. This was not only instilled by his service as a medical ward for the disabled at Hartheim Castle opened by the Nazis in 1940. No, Schloss Hartheim had neither been the source nor terminus. There had been the Hitlerjugend just before, and even prior the arrest and disappearance of school friends and their families in Frankfurt during Kristallnacht. No matter the interminable number of terrors witnessed and enough to kill the spirit of most boys, Ulrich Hoffstetler’s nimble sense of adaptation coalesced around a core of listening to the whisperings of death. Death was the grand arbiter and explicable when nothing else seemed to be. It made ultimate sense. Life, on the other hand, was capricious and a vagary. Life trembled with senselessness. Hoffstetler had never been in essence a survivor directed by the end of days. He had been a Nazi only by the necessity to follow a national directive to be so. He had only been a facilitator of lethal injections given to the infirm and insane at the euthanasia center of Hartheim only because he had been assigned to such a post. And as an observer only, Ulrich Hoffstetler had easily willed himself not to shudder at the memory of exploding fiery debris falling atop those Jews huddling on the sidewalks scrambling to escape the destruction of Frankfurt’s Borneplatz Synagogue during Kristallnacht. Nothing had ever compelled Hoffstetler to crack and leak vital fluid. He moved through life at every turn with mechanical fluency, no matter the horrors surrounding him. Nothing much surprised nor frightened nor upset him or his conscience. However questionable that conscience might be judged, he was socially agreeable by nature and this spared him undue scrutiny. There was an elegance to his speech and he was a polite listener. The outward expression of his existence did not propagate disturbance and sought to resonate harmoniously within the social milieus he found himself. Hoffstetler’s successful attempts to meld socially came more the harmless tweaking of the physics of sociability and never through the con. That many Nazis had easily crossed the permeable membrane from war time Europe to post-war America was commonplace knowledge to Americans themselves, and there were enough German-Americans everywhere that had already helped create and sustain America’s sense of pride and accomplishment that whether they had come to America before or after the war didn’t cause a ripple’s difference in social terms. Ulrich masterfully kept a low profile just in case, though, never drawing attention to his past. Even marriage and fatherhood boiled down to mastering a set of sanguine-inducing algorithms Hoffstetler learned by seeming rote from everyone he had ever known who had ever had success at it all. Marriage, in particular, he had early on decided must be thought of as a working arrangement; an agreed upon separation of responsibilities and mutual respect for the domains each partner owned dominance of. He took full accountability for his responsibilities and chose a wife by design that would keep to her own and fulfill her role in same. As for being a father of an only son, Hoffstetler knew that if he simply was present when needed and provided seamlessly that his son would love him for the graces of contiguous stability he provided as the head of the family. Hoffstetler knew best that every human being he had ever known needed a family more than did he himself. He took all things human on the basis of experience external to himself and never took seriously that he should be what he needed based on some naturalistic, individual assessment. Follow the statistics of what human needs demands and plot yourself upon the line that cuts through the scattered dots on a graph of linear regression. Hoffstetler appeared born to carve out a linear path as directed by the statistical algorithm so described. His housekeeper barely noticed the man she took care of because he barely showed himself to the world. He was the world some degrees removed, for that matter. For the housekeeper, who had no problem with the world- why would she have a problem with a man who was more iconic of the world in toto than he was a discernable individual? It was as if she were taking care of a mental note she carried in mind based on an article about how to take care of the elderly- detached elderly care, as it were. She liked it that way, and, of course, so did Ulrich Hoffstetler. All things were what they should be for the housekeeper, and Ulrich of course had hired her full well knowing that she would loyally remain because she needed an employer first and foremost who would fulfill the perfect role model of an elderly charge who would never create complications. Hoffstetler had crafted a simple set of questions at her interview which covertly tested just what it was that would make her serve for the long term. The trick was to recruit someone whose credentials and references spoke for themselves. This left only the important task of measuring compatibility as the applicant for housekeeper would be a live-in position. So Ulrich Hoffstetler sat with the then-applicant Sarah George in a sunny breakfast room where he spent breakfast every morning and holding her application in hand asked the following: “I see you have never been married.” “Yes, that is so.” “May I call you Ms. George?” “Yes, sir.” “Let me see- this application tells me you are fifty-five years of age?” “That is correct.” “What hours do you most naturally keep?” “Waking at five and to bed by nine thirty.” “Does peace and quiet suit you?” “It suits me fine, sir.” “What kind of home do you wish to work in?” “One of order and predictability.” “What brings the best out of you?” “The quest for cleanliness.” “Give me a typical menu for the meals of a day.” “Oatmeal with raisins and bananas topped with cinnamon, vanilla, and nutmeg for breakfast. Egg salad sandwich with sweet pickles and tomatoes for lunch. Poached salmon, braised asparagus, and a vinaigrette salad for dinner.” “What do you do on off hours?” “Embroider and read.” Based on two written recommendations, eight interview questions and one interview confirmation Hoffstetler knew without a doubt that Sarah George would be a housekeeper of remarkable distinction. Ulrich and Sarah would never sound right together as two names sharing the subject of a conversational sentence. That there was a cat, a parrot, and a nurse who reported daily to help administer to Hoffstetler’s daily regimen of medication more or less rounded out a plausible household of inhabitants. As for the third party, Erika Jansen was the old man’s ministering nurse who injected a modicum of life-giving energy into the small, tidy rooms of Hoffstetler’s house. She was in her early thirties, healthy as an orchard in bloom, possessive of a crackling intelligence, a happy wife, and loving mother. Her daily round was to drop in and give care to a manageable number of aging, homebound seniors who, much like Ulrich Hoffstetler, were wealthy enough to live on their own by means of family support or by the help provided by a housekeeper. Hers had not always been, but was for the time being a most manageable life, no less made so by the short walking distance between her own residence and all those she visited throughout the week. It was here in an unassuming neighborhood in Phenolica, a suburb of sorts situated between the ocean on the west, a greater metropolis to the south and to the east and north an even greater mountain wilderness rising up out of river-blessed agricultural plains and valleys, that Erika Jansen was living out a quiet but meaningful existence based on humanitarian work and domestic bliss. Hoffstetler’s medical needs had recently grown to the point that he now needed a nurse to drop by once a day. His increasing propensity for nodding off to sleep without warning left him concerned that he would forget to take the correct assortment of pills in correct dosage every day. Some medications were required once or twice daily; others three time a week. He naturally used a transparent plastic pill sorter with four pill compartments provided for every day of the week, and just a couple of years previous had still been able to refill it faithfully and with accuracy. But Hoffstetler knew that he was slipping and that he could not trust himself any longer. Erica Jansen took care of this and also filled his prescriptions. Hoffstetler needed someone to bathe him as well, and he had retrofitted his master bedroom’s bath with a special shower and toilet that allowed for a man who could barely stand up on his own to both bathe and use the toilet with the aid of someone else. Sarah George had been given an upstairs bedroom and bathroom of her own. Her room overlooked the shady street below, lined with oak trees and tall hedges behind which well-manicured lawns were sure to include well-spaced rose bushes within their prescribed borders. Hoffstetler had for years spent most of his active hours in his library, adjacent to his bedroom as adjoined by a set of opposing glass-paneled doors. Built-in book cases lined the walls, full of hardbound books and personal papers. A long desk dominated by the double monitors of a very fast computer system made up the working core of the room whose floors were dark stained oak. Modernity as mined from the brushed aluminum encasements of his computer and its peripherals cushioned him to virtual safety enabling Ulrich Hoffstetler to keep his aging blood’s tide high riding astride the wild bronco that was the physical world once removed and continuously mediated, reduced to sound and vision on a high definition computer screen. Naturally it would follow that it was the aging papers as stored in large anonymous looking dockets on the book shelves that Hoffstetler found less and less useful. That hi-technology made his paper documents non-important was convenient. Oh- they were safe from destruction- having been scanned and digitized long ago. It provided an easy palliative to the dread that he would prefer not to acknowledge their existence. They were like shadows thrown behind the computer; a convenient backdrop whose appearance paid its respect to the idea of a serious man with an archive while the hard bound books provided the irreplaceable aesthetic of the old world library. There were three dockets on the top shelf of the hardwood bookcase, entitled Micah I, Micah II, and Micah III. Why would the old Nazi, ward intern to the doctors of death at Hartheim Castle name his son after a Jewish prophet? Well- a minor Jewish prophet in all truth. Perhaps an appeasement to the Holocaust? No, there were both historical and aesthetic reasons for naming his child Micah. Careful premeditation was Hoffstetler’s way. Whatever the choice it must make beautiful sense to qualify as his male child’s name. The name Micah itself possessed a beautiful ring. As homonym with the mineral, there was a physical appeal. God, too had commissioned the prophet Micah to come out and denounce the evils that had taken hold of Samaria and Jerusalem. The consequences of the wickedness comprised his prophesy. "Evil cannot befall us," Micah beseeched. If the Jews continued their evil ways "Zion shall be ploughed up like a field, and Jerusalem shall become ruinous heaps, and the mount of the Beth-Hamikdosh forest-covered heights!" They did not listen and were destroyed by Babylon one hundred and thirty-three years later. Hoffstetler knew his prophets though he was an atheist. Religion as a path to redemption was anathema to Ulrich Hoffstetler; but religion as history was a wonderful tool for quickly accessing philosophical wisdom. Micah held enigmatic meaning as a word. In Hebrew it was a taunt, asking “Who is afraid? Weakened? Disheartened and cowed?- Are you a wuss?”. It was also for the Hebrews the pregnant query “Who is there?” It was Micah who was there- and he was brave enough to ask if you were brave enough to claim existence. Micah embodied the concept of calling people out. Hoffstetler was supremely pleased by this. With dismissive irony Ulrich, the former Nazi, named his only child Micah. The second part of the story behind the name began in Austria in a Tyrolean castle when Ulrich Hoffstetler was seventeen years old. The land upon which the castle stood had belonged to nobility since the eleventh century. Schloss Hartheim itself was built in the early seventeenth century. It was a famous Austrian landmark; a classic Renaissance castle. The castle changed hands in the early nineteenth century and in 1896 was offered to the Regional Charity Association by its last noble owner. This society decided two years later to transform the castle into a home for ‘Schwach und Blodsinnige, Cetinose und Iditen’ (Mentally Defective and Feeble-Minded, Cretins and Idiots). Schloss Hartheim, which had once housed nobility had been given over to the warehousing of the mentally ill. The work carried on by the home’s doctors between 1898 and the eve of World War II was in accordance with the Hippocratic Oath. But in February 1939, the Nazis, now in full control of Austria, seized the castle. In early 1940, Schloss Hartheim was retrofitted and became one of six newly instituted euthanasia centers, the first facilities of which were to be used for the mercy killing of both mentally defective adults and children. Just after the opening of Hartheim’s euthanasia center, Ulrich Hoffstetler, a young upstart in the Hitler Youth both driven by ambition and looking for a way to avoid orders for frontline duties in an escalating war, ingratiated himself upon a Hartheim doctor who happened to be visiting a Youth rally. The doctor’s name was Rennaux, an acclaimed physician who ranked high in the Reich regime. He was the father of Hoffstetler’s best friend, a fellow Youth with whom he trained and served. Something appealed to the young man about working in a real castle. Asking for the permission to interview for a staff position at the hospital, Hoffstetler received agreement and took the train from Frankfurt to Linz, Austria in the spring of 1940. Poland had been invaded in September of 1939. The war was on and Hoffstetler’s conscription loomed any day. As a member of the Hitler Youth he was already registered with the Wehrmacht. Hoffstetler wanted no part of infantry life and to be put into harm’s way. He knew intimately through his confidential friendship with Dr. Rennaux’s son that medical doctors were amongst the most important and powerful members of the Third Reich. Given the vital importance of ideology to the Third Reich, doctors’ services and advice carried as much weight as did the commanders of the Wehrmacht. The struggle was not only carried into military battle but as well into the homes of all Germans who families seeking to root out and destroy polluted, degenerative genes. Hoffstetler also knew that Dr. Rennaux was a deputy director of Schloss Hartheim, a hospital which had just opened in the beautiful Tyrolean area of northwestern Austria. The timing was critical, and Hoffstetler knew he must vie for employment there immediately as staffing was still in process. All of this vital information came the way of Dr. Rennaux’s son. The work at Linz and Hartheim was a secret operation. The public had not yet been properly desensitized to the killing of especially children based on eugenic principles. The Third Reich was sure that the open killing of undesirables would eventually become accepted especially accelerated by the fact the country was on a firm war footing, but in the meantime, secrecy surrounding Schloss Hartheim. Hoffstetler himself had only been told Hartheim was a hospital. For the Nazis and the team of death doctors they had assembled the operation of a euthanasia center was experimental in nature, attempting through a variety of trials to find the quickest, cleanest way to kill large groups of human beings and dispose of them with minimal trace. Dr. Rennaux risked bringing Hoffstetler on site based solely on his own methods of recruitment, and though it did not follow human resource protocol, he exercised his deputy directorship to do so. The doctor needed reliable staff that he could personally vouch for. The institution was behind schedule for full staffing as the rush order to open the center had strained human resources. Rennaux did not necessarily trust the given provisions for staffing the center. He knew through his son and other sources that Hoffstetler was a qualified candidate; rather the calm, cool, and cold blooded type but a zealous patriot as well. The doctor looked for these qualities that preceded Hoffstetler during that first crucial meeting. Rennaux was particularly keen upon observations of Hoffstetler during the castle tour. The litmus test would be the Youth’s reaction to the sights, sounds, and smells of two inextricably related functional spaces in the castle: first, would there be composure when first walking into a ward filled with idiots and cripples- almost all of them children; two, will Hoffstetler keep his cool in the rooms of death. They met in Dr. Rennaux’s office, and Rennaux directly took Hoffstetler into the castles’ grand, open lobby courtyard. The open air columns and vaulted arches running along the porticos supported the three floors with a clear view to the fourth floor and the building’s ceiling. The two quickly ascended the staircase to the third floor. Quite suddenly, a nurse threw open a door and Hoffstetler was ushered into a hospital ward. Litmus test one: He did not flinch, wince, nor show any outward sign of disgust, fascination, empathy nor any other emotion one might expect of most human beings upon being introduced for the first time into a large ward room housing dozens of young, forsaken bodies and minds twisted by a soul numbing array of deformities. Dr. Rennaux patiently took Hoffstetler from one bed to the next. The moment of truth was to have Hoffstetler walk up and prompted to closely inspect a young person whose mental facilities were perfectly intact but whose physical deformities qualified him as a “wasted life”. Hoffstetler looked on as if he were inspecting animal stock at a regional fair and fest. Dr. Rennaux let Hoffstetler mill among the ward’s patients for a full hour. Taking the pace slowly he explained the separate conditions of perhaps two dozen patients. Meanwhile most of the patients cooed, gurgled and mumbled unintelligibly. Rennaux carefully chose patients who suffered from representative conditions. He patiently gave Ulrich Hoffstetler a brief but complete historical view of the Third Reich laws that had necessitated the opening of several euthanasia centers. “When the Der Fuhrer came into power in 1933, how old were you, Ulrich?” “I was eleven years old.” “Perhaps you were unaware of the threat to the German race at that time. Am I not right, Ulrich? Still enjoying the veil of childhood innocence. Not yet a member of the Youth, were you? Der Fuhrer was wise to inspire the laws that quickly began to save Germany from genetic pollution. It was doctors especially who had alerted him of the threat. He listens to us. Now that you are part of the Youth, I know their programs have taught you well about such dangers and more.” “Yes, Herr Dokter.” “Let me be clear about what you see before you here in this ward. Granted, it must be a shock. Not every day do we see such a concentration of those whose lives are unworthy of living. I want you to understand how the Third Reich has heroically and systematically approached the threat of the German race’s genetic pollution. “In 1933 the first great genetic protection law was passed- the Law for the Prevention of Progeny with Hereditary Diseases. To protect future generations and to improve the German race the nation was ordered to separate, exclude and sterilize those who suffered from congenital feeblemindedness, schizophrenia, hereditary epilepsy, manic-depressive psychosis, severe alcoholism, hereditary deafness, hereditary blindness, severe malformations, and Huntington’s chorea. Of course, I have forgotten perhaps the greatest scourge- schizophrenia.” “Later the law was expanded to include habitual criminals and involuntary abortion of a fetus carried by a mother with hereditary illness.” “Yes, I remember a few years ago about a female cripple in our apartment building in Frankfurt who became pregnant,” Hoffstetler interposed. “It was a scandal. She was not married. Perhaps she had been raped. She had an abortion. They tried to keep it secret, but we found out.” Dr. Rennaux continued the litany, unperturbed. “In 1935 the Marriage Health Law forbade persons to be married if they were considered to be carriers of hereditary degeneracy.” Rennaux took a breath followed by a short pause of silence. “Maybe you are not aware because the following directive has only recently been declared, Ulrich. The Reich Ministry of Interior has just ordered midwives and physicians to report at childbirth the family history, hereditary diseases, family alcohol or substance use, and infants born with such conditions as hydrocephaly, missing limbs or bifida of the head and spinal cord, and paralyses. “I am one of the doctors to whom those reports are submitted. A group of us so assigned make the decision as to whether those children should be euthanized or allowed to remain home.” Dr. Rennaux paused yet one more time and looked at Ulrich with great intent. “Ulrich, all these children you see here- would you agree their lives are not worth living?” Ulrich Hoffstetler did not answer immediately. He slowly scanned the room, looking at the useless, paralytic limbs, spinal tails, mangled teeth extruding from lipless mouths, lifeless stares from hollow eyes, pin heads, and drool trickling from the corners of mouths. “We cannot allow these genes to pass on to the next generation,” Hoffstetler said rote-like with insincere sincerity of what he imagined should be said. Just as he finished speaking, Ulrich Hoffstetler heard a small voice to his right. “Who are you?” It was weak and plaintive but persistent as it asked once again. “Who are you?” Ulrich was hesitant to acknowledge, but he turned his head to look from when the voice came. A small boy with splayed feet and a bifida of the spinal cord at the neck lay on his stomach, his head on its side and eyes trained on Hoffstetler. Hoffstetler approached him and looked at the clip board and attached form hanging from his bed. Micah Adamsky, the chart read. Ulrich Hoffstetler wanted to answer the boy, but he quickly thought the better of it, deciding distractions as such were hardly warranted. He took one more look at the boy, who was now mute, and once again gave Dr. Rennaux his undivided attention. “Prevention will cleanse the nation’s blood lines, Ulrich. This is a noble cause. In 1933 we started with sterilization. But the problem is much larger; more widespread than we had realized. A true demographic of the disabled and mentally retarded was statistically calculated after Der Fuhrer came Chancellor. Now that the Third Reich has finally put our great country back on the track to economic recovery and industrial redevelopment, we can institute policies that will truly strengthen and make our race great according to the modern methods of the 20th century’s single greatest resource- science. This will both create and preserve our place as the predominant force in Europe, if not the world. “And so it is for this greater good that we must show both mercy for our Germany and these malformed beings as well. I have a book for you, Ulrich. It is a gift from me. Here, take it and read it as soon as possible.” Dr. Rennaux reached deeply into his doctor’s white coat pocket and brought forth a leather bound edition, giving it to Hoffstetler. Ulrich Hoffstetler was flummoxed. A gift from the great Dr. Rennaux on their first official meeting? He couldn’t feel more honored and proudly impressed. Allowing the Destruction of Life Unworthy of Living by Professor of Psychiatry Alfred Hoche and Professor of Law Karl Binding,” Hoffstetler read slowly and clearly, out loud. “Thank you, Herr Doctor! I will read this straight away when I return home.” Dr. Rennaux smiled. He then raised his arm, and pointing the way, ushered Hoffstetler out into an adjoining hallway. Rennaux closed the ward doors and the two of them were left in sudden silence in an empty corridor. “Once again, what do you think of the lives these poor unfortunates lead, Ulrich?” asked Dr. Rennaux. “It will never be a productive life. So it can never qualify as a good life.” “Can you imagine the cost to the state and to the society to support them?” “It is a loss for all of Germany, Herr Doctor.” “Good. I now need to show you two important places down this hallway, Ulrich.” Along the freshly painted white, third floor portico which over the balustrade offered a beautiful architectural view of the vast castle courtyard, Dr. Rennaux led Ulrich Hoffstetler to a pair of double doors. It was perfectly silent save the percussive sound made by the hard leather soles of their shoes in contact with the concrete floor. The doors were thrown open and there was an anteroom. Through the anteroom and another doorway was a room with large diameter black pipes fitted into the walls designed to fill the room with the pipes’ exhaust. “Yes, I’m glad you understand. You see, we are simultaneously doctors of mercy and agents of economic betterment, Ulrich. We must end the suffering of the irreparably damaged disabled while staunching the economic bleeding they cause for the Reich. Our charge is to humanely end the wasted lives of these creatures who have been forsaken to sub-human conditions. Do you believe you can faithfully help serve such responsibilities?” “Oh, yes, Herr Doctor. I believe in your mission and am ready and able to serve the cause.” “We deliver the passing of our patients in this chamber, Ulrich. The gas comes out of those pipes. Of all our options, this is most painless.” Ulrich stood and stared and though he did not show it there was a flutter in his stomach if only for an instant. Dr. Rennaux stood still and quiet for a moment. He then invited Ulrich to move on to the second and last room. The walls of this last room tenaciously held on to the stench of death. This was the final stop to oblivion and death without a trace. It was an ugly, utilitarian concrete constructed space with arched ceilings and windows of thick, opaque glass gridded over with metal bars. The floors and walls were stained dark which repeated attempts to clean had failed in eliminating the stains. Steel trapdoors of different sizes were seen fitted into the concrete floors. This was one of the Third Reich’s’ first functioning crematoriums. “We cannot return the bodies to the outside world, you must understand, Ulrich. It is here that we cremate the corpses. It is better that way. This provides the clean-up needed to maintain proper hygienic for the center.” The miasmal of death that was to linger a lifetime was the price of one interview. But there would be plenty more to come, and time to become so accustomed. Hoffstetler did what he could to close off his nostril passages within the confines of the hellish space and his stomach churned into knots. He stared straight ahead, poker faced. Dr. Rennaux did not lift his gaze from Hoffstetler for a long minute. He then politely ushered Hoffstetler out of the crematorium. “The job position we need filled is that of ward assistant. The job entails many tasks. In essence you will do anything a supervising doctor or ward nurse asks you to do. The nurses feed and clean the patients until they are ready for dispatch, but you will be asked to do other more physical tasks that include mopping floors, other sanitation-related duties, and helping move patients in and out of the ward. Some patients are bussed offsite to other centers that function the same as ours. You will need to help move them downstairs and out to the busses. Conversely, you will help inpatient bus loads enter the facility and settle into their assigned wards. Are you interested in such work? Think about it for a minute while we walk down to my office. It is entry level and in all honesty is drudgery. I know you are a smart, well-educated young man, but you must show your mettle. You can do that by showing that it is very important work you are doing for Germany. And it can lead to promotion most directly to becoming a doctor’s assistant. They have a higher ranking than the nurses.” Hoffstetler was led downstairs to the administrative offices on the ground floor and into Dr. Rennaux’s small but comfortable office. Hoffstetler was offered a seat and Dr. Rennaux sat opposite him at his desk. Dr. Rennaux took a pipe from his pipe rack, filled it with tobacco from a humidor, tamped it down, clenched the stem between his teeth and lit a long, sulfur-tipped match. He let the flame take hold and them lowered the match at just the optimal angle for lighting the tobacco but not burning his finger. “What say you, Ulrich? Keep in mind that whether you say yes or no you have been shown something kept secret from the public. It will take time to socialize the work we do with the greater public. But in time all good Germans will understand how important the work is that we do here. But in the meantime, you carry on your young shoulders the grave responsibility of complying to a non-disclosure agreement that comes with this interview. Breaching that agreement can lead to your imprisonment. I have taken the risk to show you because you come highly recommended by your Youth commander, as well as my son.” Ulrich’s spine stiffened while straightening. Delivered out of a fetid crematorium into the confines of a comfortable office space filling with the pungent sweetness of cherry tobacco smoke, Ulrich Hoffstetler regained full vigor and became wholly self-possessed once again. “Oh, yes, Herr Doctor,” he answered proudly. “I gladly accept this position if so offered me on behalf of you, good doctor, Schloss Hartheim, and the Third Reich.” Ulrich Hoffstetler signed the non-disclosure agreement, was given a promissory job offer letter, and rose to shake Dr. Rennaux’s hand. On the wall behind the doctor was a poster featuring the eugenic program’s poster child- the image of a stunted idiot in a Charlie Chaplin-like suit with a smiling physician in white coat behind him captioned by, “60,000 Reichsmark is what this person suffering from a hereditary defect costs the People's community during his lifetime. Fellow citizen, that is your money too.” Hartheim was part of the first wave of mercy killing unleashed in institutional cover under the Nazis. Eugenics was first manifest as a sterilization program in 1933 and over a calculated number of years culminated with the advent of war in 1939, became “mercy killing” at the hands of the State. Schloss Hartheim opening was coincided with the unfolding the Nazi plan to organize a secret operation targeting disabled children for death. So it was as a seventeen-year old Hitler Youth that Hoffstetler found himself drafted into service at Schloss Hartheim based on not only his successful interview but also the superior results of his intelligence and achievement testing. Dr. Rennaux had plans for Ulrich Hoffstetler. Hoffstetler was escorted out of the building by guards and shown his transportation. Before Ulrich Hoffstetler boarded the vehicle assigned to take him back to the train station, turned back and looked up at the block symmetry of Schloss Hartheim with its corner turrets. For some strange reason, and for all that he had just seen and heard and understood; for all the success the meeting with Dr. Rennaux wrought, it was the name Micah that preoccupied his thought and rang most clearly in his mind.

Chapter II

“So I control myself and choke back the lure of my dark cry. Ah, who can we tum to, then? Neither angels nor men, and the animals already know by instinct we're not comfortably at home in our translated world. Maybe what's left for us is some tree on a hillside we can look at day after day, one of yesterday's streets, and the perverse affection of a habit that liked us so much it never let go.” Duino Elegies, The First Elegy Rainer Maria Rilke

One of Sarah George’s favorite rounds was grocery shopping, which she always combined with her favorite form of exercise- walking. She always took along a wire carriage basket on wheels that folded up for convenience of storage. She liked the soft yet high pitched squeal its wheels made as it rumbled along the uneven sidewalks of Phenolica on the way from Ulrich Hoffstetler’s house to the local Shopping Bizarre. The bizarre was bizarre as in extravagant, and always a pleasure to visit for someone like Sarah George. Shopping was the greater thrill perhaps, but browsing was equal in enjoyment. There were two dozen proprietors in the maze of shops all sharing a common roof, selling an endless array of fine foods-local and imported cheeses, wines, freshly baked breads of every kind and description, fine local meats, a farmer’s market of fruits, vegetables, nuts and honey, and a few bakeries. Ulrich Hoffstetler knew a way into Sarah’s heart was through her stomach, and when helping her organize the weekly meal menu for his small household always encouraged her to buy something special for herself. He could afford to be generous. And he could hardly fail to keep Sarah George pleased. She especially liked Greek food- feta cheese, domales, quality olive oils and traditional dishes such as moussaka. What could be more delicious than a casserole of eggplant and ground lamb with onion and tomatoes bound by a white sauce and beaten eggs? Sarah George always shopped in the morning around 10 AM when she knew all the shops were opened and most had received the day’s shipments. By 10 Ulrich Hoffstetler had been fed breakfast, the dishes were safely stowed in the dishwasher, and any laundry needing done was already in the washer. She usually shopped four times a week as fresh vegetables were always a priority. Today’s shopping list included veal, string beans, potatoes, mushrooms, pasta and a bottle of rich, white pinot gris. To buy an imported wine could be construed as betrayal in Phenolica, so Sarah George made sure the pinot gris was at least local to the state if not Phenolica. Along with adjoining valleys nestled into the large rolling hills and scattered tall, rocky peaks in the area, Phenolica was one of the state’s great wine regions. Decidedly white, middle to upper class, conservative and home to an aging population which included a slow but steady influx of retirees, Phenolica was a small boutique city, featuring boutique agriculture (vineyards), boutique shopping (such as the Bizarre), boutique county fairs (with plenty of llamas and alpacas on display), and monthly jazz concerts (mellow but still ‘outside’) at one of the favorite local boutique wineries. Sarah George had been born in Phenolica, grew up in Phenolica, and had lived her whole life in Phenolica. Though she had never found love and marriage in the town, it mattered little. She planned on remaining in the town until she; well- until she was no more. On a given Saturday morning, Sarah George left to go shopping. Ulrich Hoffstetler knew just how long Sarah George would be gone. Her return trip was invariably two hours in duration. There was a window of time for him to pursue private activities. Hoffstetler decided to do something he rarely did, and that was to exert the massive energy needed to reach up onto his book shelf and take down an archive volume of Micah’s collected writings. Steering his wheel chair over to a corner, lower shelf of his massive book case, Hoffstetler locked the chair’s wheels and arms trembling, leaned forward, struggling to grab secure hold of a large archive box labeled Micah III. Pulling it onto his blanket covered lap, he pivoted the chair around and wheeled back to his massive desk. He leaved through the uneven compilation of loose-leaf papers stored in the archives box folder, most of which differed in paper quality, weight, size, and color. Some looked still fresh, others were yellowing; still others were stained with coffee and food. There was an easy find in the middle of the pack, a pink, stapled clutch of lined notebook paper bordered with multi-colored flowers. It was the type of paper favored by school girl. Hoffstetler turned to the third page and started to read:

January 5, 1997

I think the man in war sheds tears but never the skin that holds his cellular identify bound to form by that thing called upbringing. He could have walked the streets unattached unabashed disaffected; a non-proprietary unowned entity; a no one that everyone could be if so wanted. So, so, so- do you want it? No, he didn’t. Didn’t want to live out a history conjured by throbbing desire as driven by endocrine biology. But what of his mother his father his siblings his friends? Where were the invisible ties of blood of kindred sympathy and conviviality and natural attraction? His mind wandered like his feet as did his shoes. The woods, the great mountains, the sidewalks whose former hand laid smoothness now rippling buckles split by the roots of trees planted too closely. It didn’t matter. The boots walked carry feet and bones and flesh and a cerebrum constantly flushed-out by surging blood and the faux-triggered, synaptic firings short circuited across what had once been thought to be impenetrable boundaries. And it was naturally like a war and it was all so natural. Humankind is always at war even if it is sitting in prayer like the pope in silence inside the gates of Auschwitz. Eternal war of opposites for without them we cannot even intellectually suppose that without contraries there is no progression. And then we up the ante and roll it over on its back. How hapless is the beetle; how helpless the land tortoise when turned over to lie on their shell. We outthink ourselves. Without contraries there is no progression- so it is the 6 and the 9; the love and the hate; the peace and the war; the wisdom and the ignorance; the joy and the pain; the life and the death. Oh, to be alive; alive and nothing more however swings the traversing weight along the axis of thought. Yet death will claim ye. Claim ye in the end that some call the new beginning. And so we need the war to have the peace; the hate to have the love; the death to give a new life. And this conundrum is nothing but nature playing out its mysterious, age-old process on yet one more level endless in example. It is the gift wrapped in entropy that keeps on giving. It is all so natural. No, he didn’t it. He didn’t want the nightmares that plagued him in his pure and clean lifestyle. Unlike when a younger man, there were no substances to cloud his vision when now at sleep. But his sleep was held hostage by the past. The new, drug-free clarity allowed passage through the portals provided by the veils of sleep to reveal the long suppressed denizens of subconscious memory. Now, to be haunted by things long past that self-medication had at least protected him from when he finally was able to retire to bed; Hauntings that were once buried in brain tissue, long gone only to rise to life; twisted in form, sight, and sound that dragged the sleeping mind into the theater of the unconscious every passing night. It still persists. Sometimes the night terrors take on what is really a metaphorical guise; but were actually pure memories so disguised like a dramatic historical fiction starring those who were once upon a time significant and central to his life. They would reiterate the wedge issues that plagued his life and times; the painful rejections; the horrid faces of pain and angers on faces of ill-fated lovers leading to breakup and breakdown. Other times it would be a mundane event or series of events; perhaps cyclic in nature but never allowed to complete; never allowed to progress like Sisyphus with the rock on a hillside only to have the stone roll to a nadir which beckoned to be pushed back up the slope once again. The inability to fulfill a simple responsibility like arriving to work on time. Finishing the passage, Hoffstetler, his hands shaking sending tremors through the pink pages, stared ahead feeling a little breathless. No matter how much time went by- and Micah had been dead for twenty years- Hoffstetler would forever find it difficult to believe that this had been his flesh and blood. But perhaps it was simply a matter of something that skipped a generation. But the manic writing style was far from foreign to Hoffstetler. He had studied poetry while a school boy in Frankfurt. His mother, Adalgisa, was a trained classical pianist, and an aficionado of modern German culture. Ulrich was born in the midst of the greatest flowering and revolution of the arts in Europe since the Renaissance. Encouraging Ulrich to fully engage in being born at such a fortuitous time, she would have him, for example, read poetry to her at night once he could properly read. She also took her small son to many art exhibitions in the late 1920’s and early 1930’s before the rise of the Third Reich. Fond of poets, Adalgisa Hoffstetler worshiped Maria Rainer Rilke and almost daily read from his Duino Elegies and Sonnets to Orpheus. She would quote lines from such poems when searching for the proper way to express a piece of wisdom to her small son. At an exhibition of Max Beckman’s paintings, Ulrich witnessed for the first time Beckman’s The Night, a masterpiece of horror depicting rape, torture and murder. In utter fright, Ulrich ran from the painting to his mother’s side. “There is so much ugliness in this painting, mama. It’s frightening and I feel ill.” She smiled faintly and speaking lowly but clearly, leaned over close to her son and quoting Rilke said, “Do not fear the darkness, Ulrich. And remember, ‘Beauty’s nothing but the start of terror we can hardly bear, and we adore it because of the serene scorn it could kill us with.’ ” With such a grounding in the German proponents of the country’s modern art movements, Ulrich was naturally aware of the Nazi attack on Weimar culture- especially the visual arts- later after his mother had died and he was a teenager. What was called a national disgrace- a total of 16,000 pieces- were confiscated and exhibited at the famous Entarte Kunst (Degenerate Art) organized by the Third Reich in 1937 in Munich. In homage to his mother, Hoffstetler visited the exhibition with his mother’s sister. Though Micah was American-born and grew up during the reign of popular art, the modern hegemon, his nightmarish stream of consciousness that bored deep into the darkness reminded Hoffstetler of the art movements he had known as a boy. Usually emotionally unsusceptible to reminders of pre-Hitler Germany, Micah’s writing triggered an uncontrollable reaction. A flood of memories washed over Ulrich Hoffstetler as a blinding cascade. He began to drown in a sea of images born of the Weimar years; a collective of his many museum visitations with his mother. He became a little breathless again. Suddenly the cataract froze as one of the fast passing images suddenly grabbed the corners of his mind’s eye and anchored into stabile, motionless clarity. Ulrich Hoffstetler immediately recognized the image as that of another Beckman painting. He loved this painting, Die Synagoge in Frankfurt am Main, a take on the famous Borneplatz Synagogue painted in 1919. He was now delivered from the onslaught and flood. Hoffstetler remembered the majestic building itself before its demise in 1938. He felt hugely sentimental about the synagogue as it was akin to the landmark that pinpointed his childhood in terms of place for Borneplatz Synagogue was the crown architectural creation in his neighborhood in downtown Frankfurt. Was the painting’s sphinxlike cat looking in the direction of a sloping-synagogue a forecast of its destruction during Kristallnacht? Some of the critics read the painting as such, and attributed powers of prognostication to Max Beckman, painter a la reader of a crystal fall, but Ulrich Hoffstetler simply remembered what a surprise and relief it was to see the painting for the first time, just after the horrible fright provided by The Night. It was the night of Kristallnacht in November, 1938- a night that saw the destruction of a thousand synagogues- that taught Ulrich Hoffstetler the irreconcilable lesson that as a youth of sixteen had to find some way of surviving Nazism. He also saw that the Jews were marked for death. Furthermore, and more importantly, he knew that the only way he could survive with his life was to find a role, and play a part in the greater scheme that was arcing in acceleration towards war, yet somehow removed from physical danger. He could only pray that he would not be drafted into the Wehrmacht. Ulrich Hoffstetler’s preoccupation with survival molded him into an entirely pragmatic young man. Ending with Kristallnacht, it naturally began at the age of ten when his mother died in 1933. With her death he suddenly was wrenched and cleaved away from her love of art rooted in aesthetic chaos and revolution- especially as in play with pre-Weimar artistic movements. His soul took on the same struggle that divided Germany during the Weimar Republic’s moment in the sun. The new order and the old order vied for supremacy. But even within the new order there was a split. This phenomenon was to be found in the Weimar art movements. Hoffstetler saw there was no real choice between fanciful chaos and rejection of the status quo versus pragmatism. This was mirrored in the New Subjectivity found in German Art- but not the Verist side. It was the Classicists a boy like Ulrich Hoffstetler was to gravitate towards, with their cool and precise bead on what some called hyper-reality. As he grew into a teenager Hoffstetler was inspired by the utilitarianism involved in reconciling design and mechanization giving birth to mass production and consumerism. The Nazi’s drive to fully industrialize German life was proof to Hoffstetler of the pragmatic good of this utilitarianism, even with the social ills associated. This was an orderly way out of the chaos set into motion by the Great War’s which destroyed so many good people as did the following depression. Still, there existed in Hoffstetler a nostalgia as found in his fondness for Beckman’s painting of the ill-fated Borneplatz synagogue. It was a brand of restorative nostalgia; a feeling of loss and longing for a stabile childhood. This nostalgia did not extend to what Germany had been, however. But he saw no concept nor tool available as borne of that time available to him in his need to survive in the new Germany. If the synagogue’s image did arise on occasion it would serve a momentary pause in life’s inexorable drive to entropy as defined by a life based upon expeditious decision making, and as such was a harmless bit of existential relief. Ulrich Hoffstetler’s father, Hugo Hoffstetler, was a remote figure who worked as a diplomat in the German Embassy in Washington D.C. Ulrich’s mother in no way wanted to have her son educated in America. Her strong-willed stance was something her husband could not impeach, and given his complete devotion to his work, he consequently rarely came home, serving as a good patriarch only through his faithful financial support of the family. After Hoffstetler’s mother’s death, his father still chose to remain in New York City, arranging for Ulrich’s continued upbringing to be carried on by his wife’s sister. It was Ulrich Hoffstetler’s uncle who arranged for his nephew to join the Hitler Youth in 1938. Ulrich Hoffstetler was running out of time. He hurriedly reassembled the Micah III archive and shelfed it with greater fluidity and grace than he had in taking it down two hours previously. Sarah George could presently be heard at the back porch whose stairs led up to the back door which accessed the kitchen. Perhaps Hoffstetler had been fortunate that his father’s genes had influenced his psychological core and life preferences more than had his mother’s, as opposed to the tragic outcome that Micah’s core had been more determined by grandmother’s than by his own father’s. Could in this family tree Mendel’s laws of genetic be applied as taught to the Hitler Youth in their handbook? And do some fatal proclivities skip generations as those same laws declare? How much of it was fate as decided by chance? How much of it was destiny decided by the sum total of life factors? Hoffstetler could only ponder forever more why it was both his mother and his son had died at their own hands.

Chapter III

“The total amount of suffering per year in the natural world is beyond all decent contemplation. During the minute that it takes me to compose this sentence, thousands of animals are being eaten alive, many others are running for their lives, whimpering with fear, others are slowly being devoured from within by rasping parasites, thousands of all kinds are dying of starvation, thirst, and disease. It must be so. If there ever is a time of plenty, this very fact will automatically lead to an increase in the population until the natural state of starvation and misery is restored. In a universe of electrons and selfish genes, blind physical forces and genetic replication, some people are going to get hurt, other people are going to get lucky, and you won't find any rhyme or reason in it, nor any justice. The universe that we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil, no good, nothing but pitiless indifference.”

Richard Dawkins, River Out of Eden: A Darwinian View of Life

“Just a reminder, Mr. Hoffstetler- Erika Jansen will be here today at 2 PM,” announced Sarah George. “Thank you, Sarah,” responded Hoffstetler, who even at his most tired, listless, or ill-feeling always managed to issue a polite rejoinder to Sarah George. Erika Jansen sometimes worked on Saturday afternoon. Her schedule indeed changed a little every week. Home calls to the elderly required flexibility. One never knew when an emergency might arise. As the mother of two young children, she was fortunate to have the services of her mother as baby sitter when her duties as nurse called. Erika was more than a licensed home care nurse. She also was a state-licensed physician’s assistant and had worked for several years in health care teams along with doctors and other health care professionals. The work was rewarding and the pay good, but after having had children she found that her career did not give her the flexibility of schedule she liked, and given her husband’s income was sufficient, she decided to pursue home care services on a part-time basis. For Ulrich Hoffstetler, what initially had interested him in Erika was her licensed status as physician’s assistant. As a PA, she could diagnose and treat disease. Even more importantly, she could prescribe and administer medicine. Hoffstetler did not like the “conventional physician” and their typical bedside manners. He also liked the idea of receiving treatment at home. He needed the care, but was militantly opposed to entering a medically staffed retirement home. There was no relative to pressure him into this, anyway, but he was bound to die at home, and would not be caught dead in a hospital if he had anything control over the situation. When interviewing Erika, Hoffstetler was very attracted to the tangential he discovered about her. Erika had a background of interests and skills beyond medicine and therapeutics. For example, she had been an avid painter as a child and teenager and her interest in the visual arts had never faded. Recently, she had taken up painting and silk screening once again. The greatest therapy Erika Jansen had to offer the aged Hoffstetler was her ease and skill as a willing conversationalist. Her interests and knowledge cut a wide swath, as did Hoffstetler’s. He always looked forward to her visitations, holding great affection both for her and how stimulated he felt when he was in her presence, even if she was poking holes in his arm in order to hook him up to an IV. Erika Jansen enjoyed the discursive talks as well, but felt a failure as a therapist. She simply could not convince Hoffstetler of the need to quit smoking. Hoffstetler said it was simply too late. At ninety, there was no reason to change life styles. Not even his chronic affliction of peripheral artery disease- which was growing worse as time passed- put the fear of God into Hoffstetler. Clearly, PAD was a result of smoking. In his early eighties, he began to limp involuntarily, and PAD was diagnosed immediately. Beside claudication, he suffered also from limb ischemia. It had been almost a decade since he had lost that battle, succumbing to life in a wheel chair. Since being so confined, things predictably had gotten worse. Hoffstetler underwent several invasive procedures. Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) had already been administered four times over a ten-year period. Stenting had successfully prevented him from limb amputation, but after a decade its days of usefulness were numbered. For the persistent smoker, arteriosclerosis was something that took hold, entrenched and only got worse over time. Hypertension was another symptom from which Hoffstetler had suffered from for forty years. Erika Jansen had decided that since her patient was loath to quit smoking, that she could impede his advancing vasoconstrictive disease best by controlling his hypertension. Medications in pill form no longer helped prevent Hoffstetler avoid acute episodes, and in such dangerous bouts of escalating blood pressure she resorted to intravenous doses of enalaprilat, or Vasotec IV. Erika Jansen knew that it only a matter of time. Her role was to medicate and entertain a dying man. Sometimes she thought it was all an absurd waste; that another patient willing to participate in their own healing would be more worthy of her services. But as she got to know Ulrich Hoffstetler she began to see him in a much broader light. Long since she had gone soft; refusing to judge him as an uncooperative patient, and instead chose to appreciate him for his refined interests and knowledge. Hoffstetler was careful not to reveal things to Erika that he naturally hid from everyone else. Since she did not probe into those darker places she quickly understood he would allow no one else to go, their conversations flowed with an enjoyable freedom monitored by discretion and restraint. On this particular Saturday afternoon, Erika Jansen first inventoried Ulrich Hoffstetler’s supply of medication. “It appears you have been both accurate and timely in taking your medication over the past two weeks, Ulrich.” “Oh yes, I try my best to keep close count; as always. The penalties one suffers for taking too much or too little are….well, you know.” “Let’s examine your legs, Ulrich. How do they feel? Are you experiencing extreme any cramping, swelling, or numbness?” This was Sarah George’s cue. She came into Hoffstetler’s bedroom and one at a time, raised up and locked the two leg extenders of the wheel chair parallel to the floor while Erika Jansen held up one leg, then the other before setting each down on top of the long, narrow pieces of cupped metal. “Oh, I don’t know. They swell and cramp off and on,” Hoffstetler answered, his voice trailing away. He was loath to admit that his legs had also been experiencing more pain when trying to sleep at night, elevated on his bed. Erika Jansen gently rolled up the leggings of Hoffstetler’s pajamas to the knee. Then she inspected his legs from above, looking among other change from her last examination, as well as degrees of swelling, new varicose veins, and skin discoloration. Both legs were markedly cold to the touch; more so than ever before. Much of the skin was shiny. Atrophy had long since reduced Hoffstetler’s calves to a mass of sagging skin. The musculature of his legs now extinct, his knees and ankle bone looked like grossly enlarged condyles. Hoffstetler did everything he could to look away and spare himself the ugliness his body had taken on during the past decade. Erika Jansen picked up each leg gently, one at a time, inspecting underneath. Afterwards, she stood, the limbs in questions laid out before her, crossing her arms and looking intently at Hoffstetler. “There is increased skin discoloration in both legs, surrounding your ankles. You feel clammy all over. There has been quick deterioration of your condition since I last visited. If this worsens at the current rate, we can assume sores and infection will soon enough follow. Intravenous infusions will no longer act as palliative. As we have discussed so often- amputation might become the only life-saving treatment. Ulrich smiled half-heartedly, while doing everything he could not to meet Erika’s eyes. “Well, let’s not sugarcoat it too much.” His feeble attempt at humor died with less than a whimper. “No,” Erika said, poker faced. “Let’s not.” Suddenly, and for the first time, Erika Jansen had lost any softness towards her patient which she had developed cautiously and surreptitiously over time. Hoffstetler looked up. Rarely did he experience abject emotional shock, but that was what had overcome him. This was not Erika’s usual kind and supportive tone he had come to rely on. “How much time are we talking about?” Erika’s sternness remained fixed. “You mean the need for amputation? I can’t say with exactitude. Perhaps a few months. You’ll have to see a specialist and have a scan. You could suffer a heart attack before amputation as far as that goes.” “And if I quit smoking now; is there a chance to turn it around?” Erika shook her head and turned her stare to the floor. “Ulrich, there is always a slim chance, more so a change in attitude embracing life as opposed to being fatalistic. But to be frank, I see the degeneracy as having passed the point of no return. You are living on borrowed time. It’s time you fully admit that to yourself. Can’t you at long last, see?” Throughout a decade of wheelchair confinement and the consumption of an additional four thousand packs of cigarettes as well as countless cigars, Ulrich Hoffsetler had taken his condition in ridiculously good stride. He somehow didn’t miss an ambulatory life. It made no sense other than that Hoffstetler had the power to shunt all pernicious reality to ground like a lightning rod. But now death- let alone mortality- was beginning to take on a discernible guise; even a persona. It was not the persona of that, the messenger, Erika Jansen, but the rise of some dark form Hoffstetler saw lurking in the natural shadows seen on the floor along the wall under the windows as the sun light streamed through to the other side of the room; or the movement of yet another dark form- one that naturally should not exist- running across the ceiling like a hallucination. These were forms without color, depth, or value added dimension according to any sense’s chosen tool of measurement. Ulrich was a man who though seeing was believing because the matter-of-fact was the only source of fact upon which our reason could rely. There would be no cheery asides nor witty repartee between Ulrich Hoffstetler and Erika Jansen today. “I will fill these two prescriptions for you,” said Erica. “I will also make an appointment for a heart and circulation specialist who after examining you will most likely arrange for an MRI scan. Prepare for this, Ulrich. Be immediately available. I’ll get back to you within twenty-four hours.” Sarah George appeared once again, her timing perfect, standing sentry as for the changing of the guard. No doubt she had overheard everything. Ulrich Hoffstetler remained dead panned silent while Erika Jansen turned and left the bedroom on her way to the front door.

Chapter IV

One light is left us: the beauty of things, not men. Robinson Jeffers

Micah saw no good reason, nor bad. He’d rather think of the blood running through his veins as clear water in river; fast running in spring; lazy and low after months of dry heat in late summer; cold and bracing in the winter. There was great beauty everywhere, but not within. The human body housed the anguish of existence. Blood instead of water. Couldn’t water just do? Micah wished he could replace his blood with water. Micah saw his ancestral past as a murky path that led through a long cave; a vast structure of subterranean stone walls silent save the sounds of scurrying creatures and mineral-rich water droplets falling from an unreachable ceiling. He was not by nature a spelunker; but few people are. What drew him otherwise against his will into the cave was his grandmother; a woman he never met; the most important woman of his life that he had never had in his life. His maternal grandmother’s name was never referred as passed his father’s lips, but Micah loved its sound- Adalgisa. “Noble hostage”. Its meaning haunted Micah almost as much as her choice to take her own life. A woman of such energy, talent, and intelligence- an unfathomable loss to not only her family but the world, over which Micah ruminated constantly. The need to find a missing link; a lost and forgotten savant; an omniscient persona who existed as the source of light and life for generations to come. Micah felt the dearth; the bareness due to Adalgisa’s self-delivery into oblivion; leaving no provision for someone like Micah who would inevitable arise in the wake of her passing. What she had to offer would have been so well-received; if only she had understood that many things skip a generation. Micah had pressed his father on Adalgisa; on pre-war Germany; on the culture of Weimar. Ulrich Hoffstetler refused to confer the secret of those times and how Adalgisa fit into them. It was unforgivable. Micah never did forgive his father for this ultimately selfishness; this self-protective niggardliness; this theft of a goddess singular to the family tree.

*

Ulrich Hoffstetler knew, of course, that his refusal to bare his past roiled his son’s blood. Hoffstetler was prepared to suffer the personal retributions necessary to hide his Nazi past- especially those eighteen months spent at Hartheim Castle, but he was not prepared to accept the large cost for which he would be liable. But the fault lines that came to define Hoffstetler’s existence started with the mangled heap of child named Micah at Hartheim. The erstwhile Micah; never to be thought of as the ersatz. He was the first child that Ulrich Hoffstetler helped kill; helped euthanize. In the interview for the Hartheim staff position, Dr. Rennaux had not divulged to Hoffstetler the most sensitive information about the euthanasia program. In August 1939 the Reich Ministry of the Interior issued a decree requiring all physicians, nurses, and midwives to report newborns and children under the age of three who manifest severe mental and physical disability. To rid the country of the burden of the incurables, the useless eaters- whether child or adult; German national, foreigner or Jew- the euthanasia program which Hartheim was part of was established by decree by Adolf Hitler. It was top secret as the Reich knew the German people were reviled by the idea of so-called mercy killing- especially as practiced on their own children. After health care professionals country-wide had reported the names and addresses of all those children under their care that suffered from potential incurable diseases, the state instructed the euthanasia medical team and their program, called T-4, to contact the parents of these children, and convince them to have their children admitted to hospitals for treatment. Deception was used as a matter of course. Ultimately the children would be killed and causes for their deaths reported back to the parents under pretense. Micah’s parents had been approached according to such lies and connivance. They felt helpless as Micah’s deformities were so severe, and when presented with an “experimental treatment” offered for free by Germany’s best doctors, they felt there was little to lose. Because Micah’s pulmonary system was so compromised due to his misshapen skeleton, the medical team knew it would be a simple task to create a false scenario under which Micah would not survive the treatment. Micah’s case was simpler than most. The morning Micah was murdered, the supervising nurse had just abruptly left her post in Micah’s ward, running to the water closet where she was sick and vomiting. The doctor turned to Hoffstetler, the ward orderly, and issued the order, “Roll that cart over here.” The small, metallic mobile cart was white with a small table top covered by a thin white surgical towel on top of which lay syringes, rubber-sealed vials of “medication”, a bottle of alcohol and small box of cotton. “Hand me that syringe and the vial on the left.” Two doctors held down the small child while the third was free but continued to order Hoffstetler. Protocol determined such overkill. The cruel ridiculousness of it even struck Ulrich Hoffstetler. Why should two grown men be needed to pin a small disable child- one who could barely move- to his bed? Hoffstetler moved closer to the group of doctors. “Prepare a cotton swab with alcohol.” Hoffstetler complied. Yet another expression of confusion. Do you really need to inject to kill so cleanly? The doctor pierced a vial with the needle of a syringe, turned it upside down, and pulled back on the syringe’s plunger, drawing back several milliliters of yellow liquid. Sliding the needle free of the vial’s rubber seal, he held the syringe vertically while pressing on the plunger, releasing whatever amount of trapped air remained followed by a clean spurt of liquid. The doctor then reached over the child named Micah. Micah was face down, just like the day Hoffstetler had first met him. Micah’s view of Ulrich Hoffstetler was unobstructed, and when Micah finally realized it was Hoffstetler, he stopped arching his eyeballs, straining to look behind him in order to see what the doctors were doing. Micah suddenly became oblivious to what these three men were doing to him. His eyes betrayed neither the fact that two doctors were pinning him to his bed, nor that a third stood over him with a syringe. Having caught sight of Hoffstetler, Micah instantly fixated on him, as if suddenly hypnotized by a vision. Hoffstetler felt the grips of Micah’s stare; a last voluntary nervous system response that this God forsaken crippled boy who had been wrested from him unaware parents thinking that an invitation to Hartheim was purely for therapeutic treatment would ever have in his very brief and tortured existence. The doctor plunged the needle into Micah’s arm. The stare remained fixed on Hoffstetler. Very quickly, Micah felt things speed up momentarily, then slow down, then nothing. But his eyes remained fixed in place, but they had started to lose their luster. His pupils dilated. His pulse was taken. No one said a word. The doctors then asked Hoffstetler to bring to them a rolling gurney. Once positioned parallel to the bed, two of the doctors slid Micah’s body over onto the gurney, and covered him with the sheet from his own bed. “You know what to do now,” one doctor said to Hoffstetler. Ulrich Hoffstetler gripped the grilled iron foot board of the bed and began to roll it over to an adjacent autopsy lab where a resident doctor who conducted examinations and experiments on both living and dead bodies would be given the opportunity to work on Micah’s corpse if he found it worthy of interest. Hoffstetler knocked on the door, and no one answered. He knocked again and waited. And then again. Confident no one was inside, he opened the door and backed into the lab, pulling the bed behind him. He parked the gurney next to an examination table, and waited for a moment. Looking at the lifeless mass hidden by a white sheet, Ulrich Hoffstetler tried to remember what Micah’s face looked like while he was alive. He was terrified to lift back the sheet and see for himself what that face looked like in death now that a few minutes had already passed since the injection. Hoffstetler had seen a few people euthanized by injection already, and the one thing he knew is that life oozes out of the pores of the skin, and the strands of the hair, and the retinas of the eye just as would blood from the veins if they had been cut and the body let to bleed out. Life drains out of the body rather quickly, but not all at once. He wanted to actually say good bye to Micah, but was overtaken by the fear that the sudden unmasking of the boy’s face would reveal just how much life was already gone over the course of time it had taken to wheel his corpse into the autopsy lab. Micah’s death; his uncontested murder- had catalyzed a colossal process in Ulrich Hoffstetler. Shortly after leaving the autopsy room, he experienced an irrevocable cleavage of his soul; bifurcated; each half driven into permanently divided and polarized other-halves. The death was powerful enough to mark him for life; as powerful as an experimenter’s first-ever fix of an über-opioid that served not to overdose but transform him into a hapless, lifelong junkie. There was no going back it seemed. His conscience and sense of empathy had been cut off from those pain receptors so normally assigned. He still knew what was right and wrong, and he knew how to express to others at least in appearance- whether he considered something right or wrong- or be casually indifferent if called for. In other words- he could act- but he could no longer feel the twinge of moral pain when faced with evil; no longer feel the revulsion or the disgust. All senses that make for human consciousness were not destroyed but disconnected from their previous wiring schema. Those parts of the brain that sense, perceive, feel, and judge all in symphony were rewired in a matter of a few minutes. Now, more than seventy years later, and as death beckoned, Ulrich Hoffstetler could still not see that it was his mother’s soul that died forever in the body of that crippled boy, and that the spirit of the “Noble Hostage”, Adalgisa, had forever been cremated along with that murdered boy’s corpse. Ulrich Hoffstetler let go his mother and his grief for her passing while paying the incalculable price of becoming an indifferent Nazi. But that loss did not satisfy compensation for the bargain of exchange. It had been much too small in the scheme of such things, and skipping a generation sought out the next in the blood line to be bled out.

Chapter V

“If I lose heart or flinch when I hear shots- that’s a sign of a false view of life.” Ludwig Wittgenstein, serving as a volunteer gunner in the Austrian army, upon being granted the request to be posted to the place where he was in most danger, the observation post ahead of the front line where he could survey the enemy guns. The Russian front, March 1916